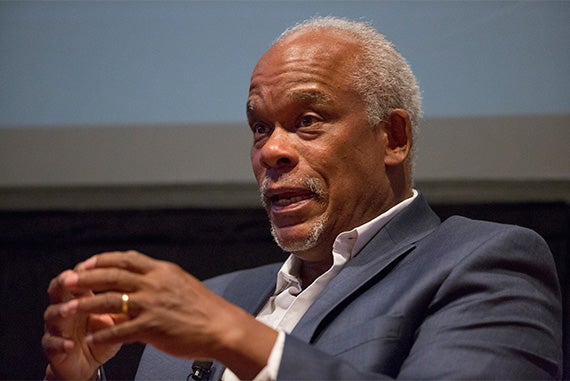

“We weren’t trying to give you any kind of new information. We were trying to give you a sense of the feeling of that summer and how people felt when the bodies were discovered,” said Stanley Nelson Jr., following an excerpt from his film “Freedom Summer.” President Drew Faust took part in a Q&A session with Nelson during the final William Belden Noble Lecture last night at Memorial Church.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

What they overcame

Filmmaker Stanley Nelson Jr. explains how he documents the Civil Rights Movement and the African-American experience

The images and the music haunt you long after they become memory. The blurry footage shows three body bags being loaded onto steel tables from cars as the song “We Shall Overcome,” the anthem of the Civil Rights Movement, plays in the background.

The scenes are part of the 2014 documentary “Freedom Summer” by Stanley Nelson Jr., a searing look at the efforts of student volunteers who traveled to Mississippi in the summer of 1964 to help African-Americans register to vote. The brief clip shows the recovered remains of three young Civil Rights workers who were murdered by the Ku Klux Klan. It also shows the impassioned eulogy for one of the men, James Chaney, delivered by Civil Rights activist Dave Dennis.

For Nelson, whose films vividly capture the African-American experience, the excerpt “was just pure emotion. We weren’t trying to give you any kind of new information,” he said. “We were trying to give you a sense of the feeling of that summer and how people felt when the bodies were discovered.”

Delivering that emotion is a part of what it takes to make a great work, said the filmmaker, who discussed his career with Harvard President Drew Faust during the final William Belden Noble Lecture last night at Memorial Church.

Past lecturers in the series, established by Nannie Yulee Noble in 1898 in memory of her husband, have included former President Theodore Roosevelt, theologian H. Richard Niebuhr, Sen. Eugene McCarthy, and Archbishop of Canterbury Robert Runcie. This year’s series included screenings of three of Nelson’s films: “Wounded Knee: We Shall Remain,” “Freedom Riders,” and “Freedom Summer.”

Part of what he said drew him to filmmaking was the realization that African-Americans rarely appeared on TV and film during his youth in the 1960s and ’70s, Nelson told Faust during the hour-and-a-half discussion. When they did, he said, they were being mocked, or exploited in “Blaxploitation” films in which the main characters were often pimps or hustlers.

“Those weren’t the people that I knew,” said Nelson, who signed up for a film class in college in the hope of bringing more positive images of African-Americans to the screen. The class fueled his interest in movie-making. After graduating from film school at the City College of New York, Nelson worked for William Greaves, a pioneer of African-American filmmaking, who became an important mentor. The fact that Greaves was “making a living making documentary films” inspired Nelson. “I saw an example,” he said.

In his documentaries, Nelson tries to evoke the same kind of cinematic flair found in mainstream Hollywood films, “making them visually and aurally exciting,” and offering the viewer “that sense right from the beginning.” That strategy is on full display from the beginning of “Freedom Riders,” his 2010 film that tracks the trek of Civil Rights activists in 1961 into the Deep South to challenge segregation laws.

In the first frames, giant blue neon letters spell out the name “Greyhound.” Later, black-and-white photos of protesters flash across the screen, as do shots of their applications to the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), the group that spearheaded the freedom rides from Washington, D.C., to New Orleans in 1961.

Unsure whether the technique would work, Nelson chose to include in the opening sequence the same protesters reading what they had written on their applications five decades ago.

“I’m a senior at American Baptist Theological Seminary and hope to graduate in June,” reads U.S. Rep. John Lewis, a central figure in the Civil Rights Movement and a freedom rider. Lewis later suffered a fractured skull during a march from Selma to Montgomery, Ala., in 1965. “I know that an education is important and I hope to get one,” his application continued. “But at this time, human dignity is the most important thing in my life.”

“A lot of times, you have ideas and they don’t work. Or you have ideas and you are scared to try them,” said Nelson. “… I’ve learned just try it and see what happens.”

In many of his films, Nelson forgoes an omniscient narrator, opting instead to allow people who experienced the story to relate it in their own words. He uses music in his works “to help move the film forward,” and he can spend years investigating a story he wants to tell. That detailed research can be tedious and time-consuming, but it can also lead to gold.

While researching “Freedom Riders,” he and his colleagues pored over FBI transcripts from a hearing about a bus carrying freedom riders that had been firebombed by a mob in Birmingham, Ala. As the flames ripped through the bus, a young boy who lived nearby captured the moment on film with his new birthday present, an 8-millimeter camera, his father testified. The man said the FBI confiscated the footage. Nelson pressed the organization to produce the film, sending the bureau a copy of the transcript when it denied the footage existed.

“Six months later, they called and said they found the footage,” he said.

“You have to continue to look with a positive approach and mind-set. You never know what you might find.”

Nelson also offered his opinion on the mainstream film “Selma,” calling it “true to the feeling of the movement.”

“I think it’s great to get the story out there any way you can,” he added.

The session’s host, the Rev. Jonathan Walton, the Pusey Minister in the Memorial Church and the Plummer Professor of Christian Morals, asked Nelson about “the moral impulses” behind his own work. He replied, “The whole point is to kind of drive us forward. … I do hope that there is something that people get out of these films that relates to their lives today.”

He said that “Freedom Riders” and “Freedom Summer” have been used by activist groups around the country and the world, and were even watched by the protesters who occupied Tahrir Square during the Egyptian Revolution of 2011.

How had Nelson “kept the faith regarding Civil Rights” while making his films, an audience member asked.

“The stories make me keep the faith,” Nelson said. “The stories are incredible. They don’t make me lose faith, they make me keep the faith.”

During the evening, Nelson also showed a clip of his forthcoming work, “The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution.” The film will run at the Brattle Theatre on April 27 as part of Boston’s Independent Film Festival.