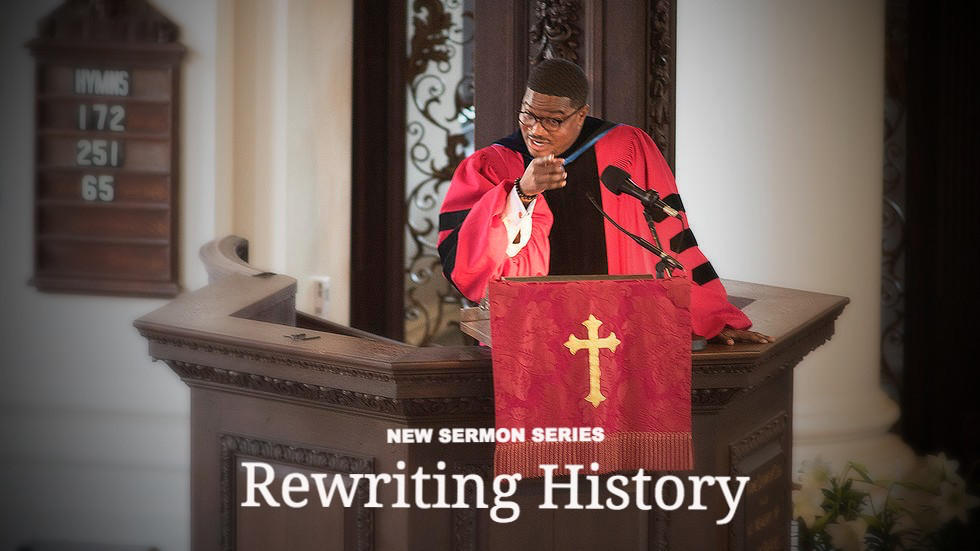

Sermon by Jonathan L. Walton, Plummer Professor of Christian Morals and Pusey Minister in the Memorial Church of Harvard University, for the Memorial Church's Sunday Worship Service.

---

“Now a new king arose over Egypt, who did not know Joseph.” Exodus 1:8

---

The book of Exodus is one of the most famous literary works of human history. It’s the second book of the Pentateuch, the term for the first five books of the Hebrew Bible. It picks up where the legend of Genesis ends. The book’s primary protagonist has become the archetype of moral courage, and a political paragon of anti-oppression. His name is Moses.

We will get to Moses in the following two weeks. But this morning, I want to make sure we are clear on how we get to this point in the story. I want to make sure we are clear about the complicated history that made the character of Moses necessary. None of us are born in a historical vacuum. You and I are not just makers of history. We are made by history. And if we want any insight into what we can do, then we should give greater scrutiny to what we have done.

The book of Exodus begins with the Children of Israel in the land of Egypt. The Hebrew people—the descendants of Abraham and Sarah, Isaac and Rebecca, Jacob and Rachel—end up grafted into the mighty Egyptian empire. Jacob, who we also know as Israel, had a son named Joseph. Joseph was a curious and queer young man. He had big dreams that his family could not contain. He wore colorful clothes that his brothers viewed as queer. He had ambitions to do more, be more, and have more. This is why others viewed him as odd.

The sort of life that others considered “normal” did not make sense to Joseph. Society’s view of success did not comfort him. His classmates could not conform him. His brothers could neither control nor contain his aspirations. Thus, his community needed to get rid of him. His brothers sold him off into slavery.

One has to wonder why someone else’s uniqueness can become a cause of great offense to others. Did Joseph’s uniqueness remind his brothers too much of something they were not? Or did Joseph remind his brothers too much of something they were? Maybe it was both. Maybe Joseph reminded them of something they were, yet lacked the courage and confidence to be openly and honestly? Maybe this was a source of great pain for Joseph’s brothers. Maybe this pain was the source of their hatred and anger directed toward Joseph. For hate is little more than the easy alternative for those of us who would rather ignore root causes. This is why, according to James Baldwin, so many “cling to their hate so stubbornly.” Because once hate is gone, we will be forced to deal with our pain.

When Joseph arrives in Egypt, the story takes a dramatic turn. While in prison, someone takes note of his special gifts. One of the king’s servants discovers that this idealistic young man with an outsized imagination can also interpret dreams. The timing could not have been better. For it was at this very moment that nightmares were plaguing the Pharaoh.

Each night the Pharaoh had the same dream. There were seven fat cows. Yet seven frail and skinny cows came along and consumed the fat cows. There were seven healthy ears of corn, followed by seven weak and thin ears of corn. When the king of Egypt summoned Joseph, Joseph provided this interpretation: For seven years there will be bounty in the land. For the next seven years there will be famine. So store up grain, crops, and water now during times of plenty, so that the nation might endure the lean years.

Joseph’s gifts, then, propelled him from the dungeon pit to the palace. He went from enslavement to authority in Egypt. His eccentricities catapulted him from condemned to commended; from misunderstood and maligned to beloved and celebrated. In fact, when Joseph’s father and brothers showed up in Egypt searching for food during the famine, Pharaoh rewarded Joseph’s people, the Hebrews, with open arms into the kingdom.

This is the first point I want to make this morning. Don’t be scared to dream. Don’t feel pressured to conform to somebody else’s expectations. And don’t be scared to march to the beat of your own drum. This is particularly true for everyone pursuing their formal education at the undergraduate and graduate levels.

Most of you learned to play by the rules. Some of you are here because you developed undeniable discipline. Others learned the requisite skills of test-taking and academic decorum. But each of us has a little Joseph in us. We have that inner voice that wants to break free. Late in the midnight hour, we envision a life that is different than our parent’s desire for us; bolder than political choices presented to us; and more creative than any curriculum our college might provide.

You know that God has put something down on the inside of you. You know that God made you different and unique in a way others may not understand. And thus you know that if you just go along with the crowd, you might just extinguish your potential gift to the world. Don’t let anyone dampen your dream.

If you don’t believe me, ask Lucretia Mott.

In the early 19th century, few expected little more from white women in America other than managing domestic affairs. Mott was a teacher who at the outset of her career became enraged that men were being paid more than women, despite the same education and training. Add to it, she felt a call on her life to preach about the goodness and grace of Almighty God—a God who for Moffett condemned the aspects of early 19th society that most Christians took for granted—denying equal rights to women, the enslavement of Africans, and the barbarity directed toward Native Americans. Most wrote her off as troubled and misguided. Many, including most women, considered her unhinged and emotionally imbalanced. In 1840, male abolitionists even barred her from the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London, lest the women’s rights issue dilute the cause of abolitionism. Yet each time someone sought to block her, she pushed harder. In Mott’s words, “Any great change must expect opposition because it shakes the very foundation of privilege.

Lucretia Mott is an incredible lesson in women’s history. You can be well-behaved. But well-behaved women seldom make history.

Don’t let anyone dampen your dream. That’s your gift to the world. If you don’t believe me, ask Bayard Rustin.

In the early and mid-20th century, he was everything one wasn’t supposed to be. He was African-American in a segregated society. He was openly gay in a homophobic culture. He was Quaker when most blacks were Baptist and Methodists. And due to his public commitment to economic justice during the height of McCarthyism, he was tagged a Communist at the height of the Cold War. Yet it was Rustin who introduced a young preacher named Martin Luther King, Jr. to the philosophy of nonviolent direct action. It was Rustin who from the shadows served as the principal organizer of the 1963, March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. And it was Rustin who worked to identify the intersections of racial, gender, economic, and sexual justice, when most activists focused narrowly on one issue at a time. Yet Rustin had both the gift of insight and foresight. This is why it is recorded that when Dr. King once suggested to Rustin that, “Maybe the times aren’t ready for you,” Rustin replied, “I am a man of my times, my times just don’t know it yet!”

Don’t let anyone dampen your dream.

Joseph was able to change the fate of his people. It all began with a dream. As Harriet Tubman put it, “Every great act begins with a dreamer. We all have to remember that we have the strength, the patience, and the passion to reach for the stars and change the world.”

But beyond encouraging you to dream, there is another point I want to make. Don’t get discouraged. Discouragement is the dark underside of our capacity to dream. This is why I noted Lucretia Mott. This is why we should remember Bayard Rustin. And this is why we should remember Joseph. But we must remember their whole story. Not just the honors and accolades. Not just the realization of their dreams, but the many dreams that were deferred. You and I have the penchant to look back at history and remember the good. We remember success. We honor achievement. But often, in the process, we rewrite history.

Think about it. This story in Exodus begins with a Pharaoh who knew not of Joseph. He knew not of Joseph’s contributions to Egypt. He knew not of Joseph’s accolades and awards. He knew not of Joseph’s prominence of place in Egyptian history and culture. But even this obscures and rewrites the complicated history of Joseph’s experience. Remember, before Joseph was heralded, he was heckled. Before Joseph was revered, he was reviled. Before his dreams were realized, they were denounced and deferred.

Never forget the underside of success. Never forget the pain and sacrifice that comes with progress. It’s easy to lift up Joseph as a hero of his people. It’s easy to talk about Lucretia Mott now as a champion of justice. It’s easy to find inspiration in Bayard Rustin receiving the Presidential Medal of Freedom long after his death in 2013. But do we find similar inspiration in the persecution they endured, the hatred they encountered, and heartbreak they suffered?

If we are going to dream about changing the world, we must accept the reality that we may first live a nightmare.

Look around. We are living in dangerous times. Twentieth century fascism is now in fashion. Klansman no longer feel the need to hide beneath hoods or computer screens. And what many thought were the bygone forces of sexism, racism, and anti-Semitism have returned to the main stage of American life for an encore performance.

Our nation has become a reprehensible reality show. Each week our President pardons more apprentices of bigotry. Each week he tells the pathetic David Duke’s, Richard Spencer’s, and Joe Arpaio’s of the world, “You’re Hired.” And each week he further depletes the vaults of democracy by insulting the institutions that protect us—institutions that serve as checks and balances on his autocratic aspirations.

I know some may say I’m veering too far into political territory here for a preacher. I know some may feel that “I came to church to pray, not to hear about politics.” But I’m here to say that this is not a matter of partisan bickering or political positioning. When it comes to certain fundamental claims on what it means to be made equal in the eyes of God, there are some things that as Christians we must remain unequivocal. Let’s not re-write history, by repeating history.

We know what happened in Nazi Germany. We witnessed what happened in apartheid South Africa. We realize the effects of the so-called Cultural Revolution in China. We still feel shame over our non-response to mass genocide in Rwanda. If we, as people of faith, don’t learn from the past, we are doomed to repeat it. We will rewrite the sadistic calligraphy of Caligula, and the cursive of Hitler, into a 21st century computer code of tyranny.

If Donald Trump’s hand-picked evangelicals want to be spiritual press agents for his foolishness, fine. If Jerry Falwell, Jr. wants to extend his father’s legacy of religious bigotry and spiritual violence, go ahead. And if prosperity preaching televangelists want to sell their soul for thirty pieces of silver, we should not be surprised. But we cannot just sit in our pews and pray silently, while the name of Christ is exploited for all the world to witness. We must dream. And then we must act.

Often so many of us say what we would have done in a previous historical moment. Most of us declare that we would have been with the abolitionists. We would have marched for women’s rights. We would have been on the front lines for civil rights. In our minds, we were all activists. We rewrite history. We place ourselves on the right side of the struggle.

But today it is not a hypothetical. You don’t have to ask where you would have been or what you would have done. But rather we can ask ourselves, where are we and what are we doing?

One day we will have to give an account to our children. They will ask, what were you doing in 2017? One day our grandchildren will ask, “what did Grandma and Grandpa say during the reign of 45?” But most importantly, one day, we will hear from the Lord:

Did you live up to and live out the dream that I placed in you?

Did you maximize the benefits and privileges that I bequeathed you?

Did you seek to deliver me, when I was oppressed?

Welcome me, when I was estranged?

Fight for me when I was Muslim banned?

Speak up for me, when I was kicked out of the military?

Provide me sanctuary, when they tried to rip my family apart.

And protect my voice when they called me fake?

Did you look out for me?

Will we be able to say, “We did it for the least of these, thus we did it for you!”

Dream. And then act!